The story of chess gets lost in the depths of centuries and in the far ends of Asia. Thousands of years ago, the game transcended the boundaries of language, religion, cultures, nationalities and classes, and managed to conquer the whole world.

The rules and moves of chess are after all so simple that any student can learn them. Everyone also quickly learns that simply knowing the bishop or queen’s moves does not lead to victory. Instead, the game involves escapes, distractions and sacrifices. There is a give-and-take of possibilities and room for creative, unexpected and clever moves. Each move leads to a different grid of possibilities, presenting advantages, challenges or risks.

It seems that the game was invented in India, as its ancient name “chatrang” (from the Sanskrit chaturanga = four divisions), describes the four divisions of an early Indian army: infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. The legend even says that when the youngest prince of the Guppa empire was killed in battle, his brother made it up by re-enacting the scene to their grieving mother. However, the first archaeological finds associated with the game, seven small, carved figures, were found in the city of Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

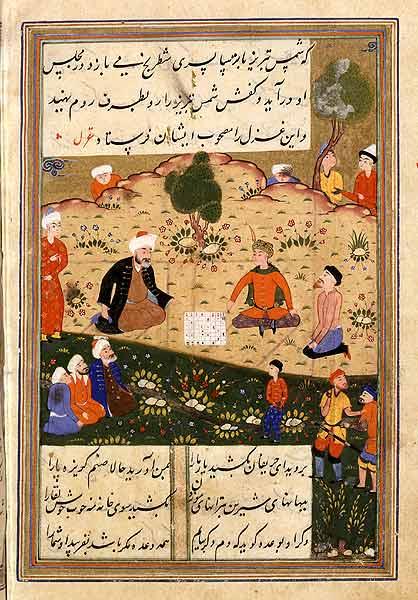

Chess spread throughout the Asian continent along the land and sea Silk Roads, along with the spices and luxury goods, and reached Europe with the Arab conquests in the mid-7th century. And while it became particularly popular in the royal courts of the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad and the Chinese emperors of the Tang Dynasty, it was not always and everywhere welcome. The Eastern Church in Constantinople condemned chess as a form of gambling in 680 and King al-Hakim of Egypt ordered the burning of all chess players in 1005.

The caliphs were themselves keen players. It is said that Caliph Harun al-Rashid conducted a correspondence chess match with the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus around 800, but that the two drifted apart – and even started a real war – when a dispute over the game began. Harun’s successor, al-Amin’s son (who died in 813), is depicted in a rumoured story: at a crucial point in the siege of Baghdad by forces loyal to his half-brother al-Ma’mun, al-Amin received a message during a game of chess. The capture of Baghdad was imminent, the messenger said, advising him that it was not the time to play chess, but to look at the city’s defences. Al-Amin told the messenger to be patient. He only had a few moves left to gain control of his opponent. It is not known how the chess game ended, but al-Amin was conquered and paid for his concentration with his life.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, chess spread to Russia and Scandinavia from the Middle East through the Volga River trade. The earliest chess excavated by archaeologists on European soil comes from Scandinavia. Shortly afterwards, chess was brought to Italy during a time of much contact and conflict between Muslims, Byzantines and the invading Normans.

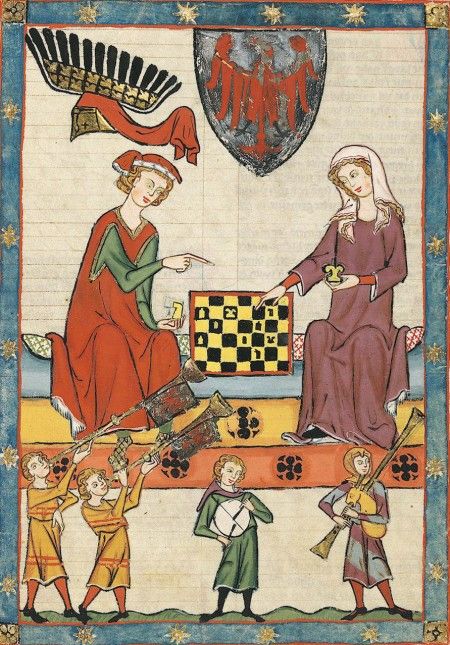

During the Middle Ages in Europe, chess was played more than at any time in the past or in the future. Among the upper classes, the game was a kind of mania – every cultured man or woman was expected to know its rules. Kings and nobles played in their courts, merchants in their businesses. The prelates of the church played equally. Chess also invaded the artwork of the time, reflected in mosaic floors, stained-glass windows and manuscripts of the Renaissance era. By the early 15th century, chess was everywhere in Europe and Asia.

As chess settled in new places, the general rules remained almost the same, but the forms of the pawns changed in many ways. Among the nomads of Central Asia, the camel replaced the elephant. Among the Tibetans, the lion replaced the king and the tiger the vizier. In Europe, the queen replaced the vizier and the bishop replaced the elephant. At the same time, the Persian term shah for the figure of the king was transferred into various languages as the name of the game itself, the Italian scacchi, the Dutch schaakspiel, the German Schachspiel, the Greek σκάκι and the English chess.

Today, the true legacy of the game that has always transcended boundaries is visible on the internet. At any hour of the day or night, one can play against hundreds of opponents lying in wait, none of whom will know the name, religion, age, gender, profession or position in the world of their opponent. Yet the longing of battle, the struggle to understand the psychology of the opponent, to escape distractions and tricks, remain as vivid and evoke as much satisfaction as they did when merchants and soldiers first took the game far from its birthplace, somewhere in India or South Asia, some 14 centuries ago.