The Lighthouse of Alexandria is one of the classic “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World”. It was still a great tourist attraction well into the medieval period, and was visited by many travellers to the city that were impressed by its magnitude.

The lighthouse was constructed in the 3rd century BC. “During the reigns of Ptolemy I and his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285 -246 BCE), Alexandria developed into a great city”. The height, form and multifunction of the lighthouse never failed to impress its visitors as it was located on the small Island of Faros, off the city coast.

The lighthouse was particularly admired and often visited and described by people from Islamic civilisation. This could be due to partly of mighty size, but perhaps also because of the interest in its technology as seen in the function of its mirrors. “Whereas pre-Islamic literary descriptions of the lighthouse are scarce, Muslim authors provide, along with various legends, valuable accounts of its configuration throughout the medieval period.”

A number of 12th-century Andalusian travelers left remarkable accounts of the lighthouse such as Ibn Jubair, Abu Hamid Al-Gharnati and Yousif Ibn al-Shaikh Al-Balawi shortly before “destroyed by series of earthquakes between 956 and 1323”. According to “Alexandria: City of the Western Mind” by Theodore Vrettos “Pharos Lighthouse most likely met its fate in the earthquake of A.D. 1365. The magnificent blocks of granite and marble toppled into the harbor and interfered with shipping for almost a hundred years before a channel was cleared of the biggest pieces. As late as A.D. 1480, the stump of the tower still jutted from the Heptastadion. Shortly after that, the sultan of Egypt, Kait Bey [Qaitbay] built a fortress and castle there, using the marble base of the fallen Pharos for walls.”

There are very different opinions on the height of the lighthouse. Because of different views, its size varies dramatically, to an extent the number roughly changes between 100 and 200 meters high. Size calculations were mostly based on the witness records of travelers from the Muslim World.

For example according to 10th-century travelers al-Idrisi and Yusuf Ibn al-Shaikh “the building was 300 cubits high. Because the cubit measurement varied from place to place, however, this could mean that the Pharos [Lighthouse of Alexandria] stood anywhere from 450 (140m) to 600 (183m) feet in height…”

Another example “The Arab descriptions of the lighthouse are remarkably consistent, although it was repaired several times especially after earthquake damage. The height they give varies only fifteen percent from c 103 to 118 m [338 to 387 ft], on a base c. 30 by 30 m [98 by 98 ft] square… the Arab authors indicate a tower with three tapering tiers, which they describe as square, octagonal and circular, with a substantial ramp”.

Overall it seems enormous in the eyes of the travelers of those times. As Ibn Jubayr witnessed it “competes with the skies in height…”

It has been said that it was seriously impaired by number of natural disasters, eventually collapsed completely and last of it remains castoff in the construction of the Citadel of Qaitbay dated back to late 15th Century. It lasted for a long time as one of the ancient wonders, alongside with the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the present Great Pyramid of Giza.

For Ibn Jubayr, the traveller and geographer from Muslim civilisation, Alexandria in Egypt was one of the first places he visited in the spring of 1183. This trip left strong impressions on him, especially Alexandria’s famed giant lighthouse, of which he had this to say:

One of the greatest wonders that we saw in this city was the lighthouse which Great and Glorious God had erected by the hands of those who were forced to such labour as ‘a sign to those who take warning from examining the fate of others’ [Quran: 15:75] and as a guide to voyagers, for without it they could not find the true course to Alexandria. It can be seen for more than seventy miles, and is of great antiquity. It is most strongly built in all directions and competes with the skies in height. Description of it falls short, the eyes fail to comprehend it, and words are inadequate, so vast is the spectacle.”

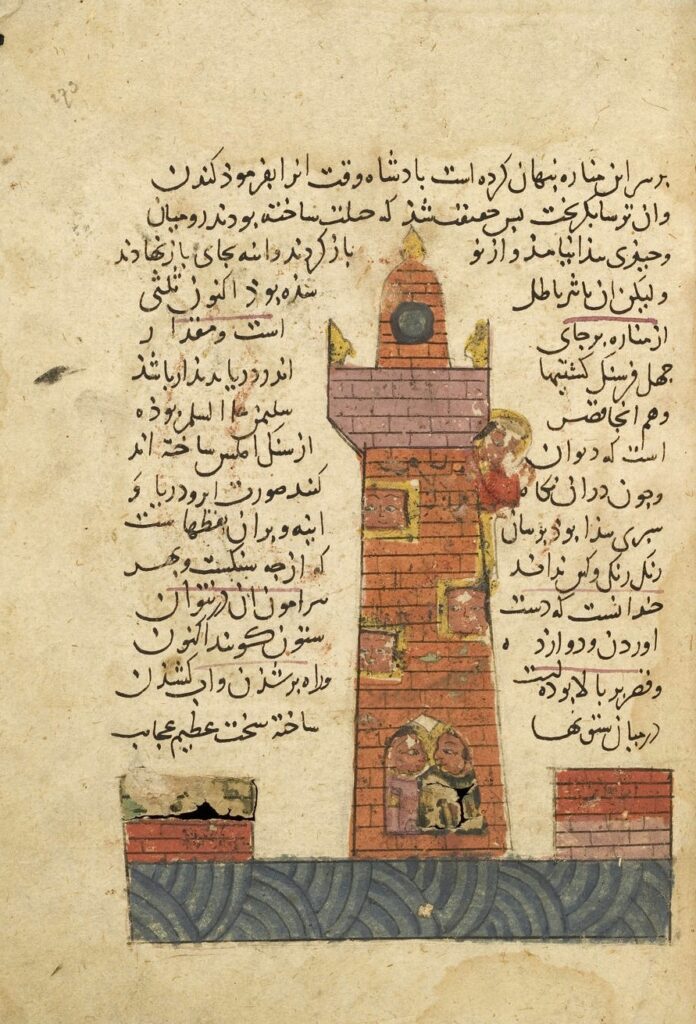

A good example of an apparently accurate drawing based on personal observation is the sketch of the famous Lighthouse of Alexandria by the Andalusian traveller, Abu Hamid Al-Gharnati. He visited Alexandria first in 1110 and again in 1117. He described the lighthouse as having three tiers:

“The first tier is a square built on a platform. The second is octagonal and the third is round. All are built of hewn stone. On the top was a mirror of Chinese iron of seven cubits wide (364 cm) used to watch the movement of ships on the other side of the Mediterranean. If the ships were those of enemies, then watchmen in the Lighthouse waited until they came close to Alexandria, and when the sun started to set, they moved the mirror to face the sun and directed it onto the enemy ships to burn them in the sea. In the lower part of the Lighthouse is a gate about 20 cubits above the ground level; one climbs to it through an archway ramp of hewn stone”.

Here Al-Gharnati refers the reader to a sketch he made. This drawing of Al-Gharnati can be shown to be reliable in the light of recent research.

The Lighthouse was particularly admired and was often visited and described by Arab writers, much more so than by their Greek/Roman predecessors, partly because of its mighty size but perhaps also because of their interest in its technology as seen in the function of its mirrors. The reference to a mirror of Chinese iron is not a fantasy but reflects the fact that medieval Arab authors were familiar with Chinese sciences and the popularity of Chinese products, in particular the so-called ‘kharsini’ in Arabic which means ‘Chinese iron’, or perhaps ‘steel’ from which mirrors were made. As for the military use of these mirrors to burn attacking enemies, stories about this are also known from pre-Islamic literature and may have played a part in the Arab perceptions of the function of the Lighthouse mirror.

AI-Mas’udi, Al-Suyuti and Al-Maqrizi are examples of writers presenting comprehensive coverage of Egypt from ‘before the Flood’ to their own time. The writings show a broad interest in all the buildings and artefacts that they saw around them dating from ancient Egypt. Their descriptions of the Lighthouse of Alexandria, of which few are known to current archaeologists, are in fact closely matched by recent reconstructions. There is a large volume of works on temples, some of which give us a clear contemporary picture of buildings now totally or partially destroyed. Medieval Arab interest in history and archaeology was not limited to Egypt but also covered other ancient cultures, where much evidence can be verified.

“The Burning Mirror on the top of the Alexandria Lighthouse which, in addition to guiding ships into harbour, had two other functions: the first being an early-warning system enabling watchers to see ships long before arrival at the Egyptian coast; the second being in cases where ships turned out to be hostile – by directing the mirror at a certain angle to reflect and intensify the sun’s rays and focusing it on incoming enemy ships, the ships would be set alight at sea. Ibn Hawqal disagreed that those were the functions of the mirror, believing the whole structure to be an observatory to study astronomy.”

“A city lighthouse with a dome on top, painted with a special chemical which, when the sun set, illuminated most of the city. Neither wind nor rain affected this light, which faded only when the sun shone.”

A lighthouse that flooded the city with a different coloured light each day of the week. The lighthouse was in the middle of a pond with coloured fish. The city was protected by talismans with human bodies and baboon heads. Nearby, a special new city had in its centre a dome, above which a permanent cloud always rained lightly. At this city’s gates were statues of priests holding scrolls of scientific works, and whoever wanted to learn a science went to its particular statue, stroked it with his hand and then stroked his own breast, thus transferring knowledge of the science to himself. These two cities were named after Hermes. This is clearly a description of what was left of Ashmunein, the centre of Thoth/Hermes, and an attempt to explain the remaining monuments based on the ancient fame of this centre.

Author: Cem Nizamoglu

Source: muslimheritage.com